It starts with an ordinary ping.

A Year 10 pupil is upstairs, headphones on, revising at the last minute. Downstairs, a parent opens an email from school and reads the line twice to make sure they haven’t misunderstood: “Your child’s homework has been awarded a mark of zero due to suspected use of artificial intelligence. This counts as plagiarism under our exam board rules.”

The shock is not just the lost mark. It’s the realisation that what looked like a clever shortcut – pasting a question into an AI app and “tweaking” the answer – is being treated in the same bracket as copying from a website. Overnight, a tool that has been casually marketed as a digital study buddy has become a potential exam offence.

Across the UK, parents are discovering that exam boards, universities and schools are quietly redrawing the line between “acceptable help” and “academic misconduct” – and AI sits bang on that line.

The “harmless helper” that suddenly isn’t

Most families met generative AI in the same way: a child raised an eyebrow at the dinner table and said, “You know I can get ChatGPT to write this in ten seconds, right?” It felt more like a party trick than a rule-breaking device. After all, everyone already uses spellcheck, translation apps and Google.

What’s changed is not that young people are using technology, but the type of help they’re getting. Instead of checking a date or a spelling, tools can now write entire essays, lab reports and personal statements in polished, fluent English. For exam boards, that crosses a red line.

In GCSEs, A‑levels and many university courses, any work that contributes to a qualification – coursework, non‑exam assessment (NEA), extended projects, internal tests used as evidence – is supposed to show what the student can do, not what a machine can do on their behalf. Increasingly, unacknowledged AI is being treated as plagiarism or malpractice, with penalties to match.

Why exam boards now treat most AI use like plagiarism

To parents, it can feel like exam boards are overreacting. To them, using AI is just “being efficient”. From the assessment side, though, the logic is blunt.

Plagiarism has never just meant copying and pasting from Wikipedia. It means using words, structure or ideas that are not your own, without clearly acknowledging the source, in work that is meant to be your own. Whether that source is a blog, a textbook, a friend – or an AI model – makes little difference.

Exam boards and regulators have three core worries:

- Fairness: if some pupils use AI to write work and others don’t, marks stop reflecting real ability.

- Validity: qualifications are only meaningful if they measure what they claim to measure – a person’s own knowledge and skills.

- Security: when assignment briefs or exam-style questions are fed into public AI tools, they can leak into the wider training data, undermining future exams.

That’s why many schools now have policies that explicitly classify generative AI as an unauthorised aid unless it is clearly allowed and referenced. The default assumption in most exam-board guidance is simple: if in doubt, a human – not an AI – should be doing the thinking and the writing.

What children must never do with AI for assessed work

Some uses of AI are now so risky that parents can safely treat them as “off limits” for any graded task, coursework or work that might be used as evidence.

Your child should not:

Ask an AI tool to write an answer, essay, report or personal statement and hand it in as their own work.

Even if they “tidy it up” or swap a few words, the underlying structure and ideas are not theirs. That still counts as plagiarism.Paste AI‑generated text into their work and then paraphrase or run it through a rephrasing app to “beat the detector”.

This is exactly the behaviour exam boards are targeting. The intent is to deceive, which exam regulations treat very seriously.Upload live coursework, controlled assessment questions or mock exam papers to public AI services.

Besides ethical issues, this can breach school and exam-board rules on confidentiality.Use AI during timed tests, online assessments or home exams if it has not been explicitly allowed.

If a task is meant to be “closed book”, any AI assistance is normally classed as cheating – just like using a hidden revision guide.Ask AI to fabricate data, quotations, sources or survey results.

Inventing evidence is academic misconduct in its own right, separate from plagiarism.

The sanctions can range from a zero on that piece of work to disqualification from the subject – and, in extreme cases, all of a pupil’s exams with that board. It is not worth the shortcut.

The grey zone: when AI can help – if your child is honest about it

Not every use of AI is banned. In fact, some schools actively encourage limited, transparent use for learning, as long as it isn’t doing the actual assessed task.

Broadly speaking, AI can be helpful for:

Explaining a topic in different words.

“Explain photosynthesis like I’m 12,” or “Can you break this equation down step by step?” can be a useful starting point – as long as your child cross-checks with class notes.Generating practice questions.

Asking for “five practice GCSE‑style questions on simultaneous equations” can support revision without touching live assignments.Planning and structure ideas.

Some older students may be allowed to ask, “What are possible angles for an essay on this novel?” as a brainstorming tool – but they must create their own plan and wording afterwards.Language and clarity checks.

Light help with grammar, spelling and phrasing (similar to what Word or Google Docs already provide) is often accepted, particularly for pupils with additional needs, provided the content is still theirs.

Where it gets complicated is not the tool, but transparency. Many universities now require students to declare any use of generative AI in a brief note or reference. Some sixth forms and colleges are moving in the same direction.

For school-age children, policies are more varied. As a rule of thumb:

- If AI has influenced what they say (ideas, arguments, structure), it should be acknowledged and cleared with a teacher first.

- If AI has only helped with how they say it (spelling, minor grammar), it may not need a formal reference – but your child should still be able to show earlier drafts.

The safest step for parents is to help children develop the habit of asking, “Is this piece assessed, and what does my teacher’s policy say about AI?” before they open any app.

Safe vs risky uses at a glance

The boundaries differ slightly between schools, but most fit the same pattern.

| Use case | Usually acceptable?* | Key condition |

|---|---|---|

| Getting a clearer explanation of a topic you don’t understand | Yes | Don’t copy wording; check against trusted sources |

| Generating a full essay, then editing it | No | Counts as plagiarism, even with edits |

| AI grammar and spellcheck on your own draft | Often yes | Content and structure must be your own |

| Brainstorming possible ideas or titles | Sometimes | Clear it with teacher; keep a note of what you used |

| Writing a UCAS personal statement | No | Must be in the student’s own words and voice |

*Always check your child’s school or college policy.

How teachers and exam boards are actually spotting AI use

Some families assume that, if AI detectors are imperfect, their child is safe. In practice, that is not how schools are making judgements.

Teachers and exam officers look at a combination of signals:

Sudden jumps in quality or style.

An essay miles ahead of a pupil’s usual spelling, vocabulary and depth of understanding raises flags, especially if classwork tells a different story.Inconsistent knowledge.

Work that uses advanced phrasing but makes basic factual errors, or can’t be explained by the pupil in conversation, is a warning sign.Text-matching and plagiarism tools.

Software like Turnitin and others can now highlight sections that look machine‑generated and cross-check them against existing sources.Follow‑up questions.

Increasingly, suspected cases are checked with a short interview or an extra written task in school. If a pupil cannot talk through “their” argument, confidence in the work drops sharply.

AI‑detection tools do produce false positives, so they are rarely used alone as “proof”. That’s why it is important your child keeps drafts, notes and plans; they are the best evidence that a piece of work is genuinely theirs.

Simple family rules: a traffic‑light guide

Instead of trying to memorise every school policy, it can help to agree a clear set of house rules. One approach is to think in three colours:

Red – never for assessed work

- Getting AI to write, rewrite or translate whole answers or essays

- Uploading live coursework questions or drafts to public AI tools

- Using AI during tests or exams without explicit permission

- Asking AI to invent data, quotes or references

Amber – only with teacher permission and clear acknowledgement

- Using AI to suggest essay structures or argument outlines

- Getting detailed wording suggestions beyond basic grammar fixes

- Using AI to summarise set texts or articles that are part of assessed work

Green – generally fine, but still use with judgement

- Asking for explanations of taught topics in plainer English

- Generating extra practice questions or quick quizzes

- Light grammar and spellcheck on your own writing

- Asking for revision tips or ways to break a task into steps

Posting these rules near the study space can make decisions faster when your child is tired and tempted to take the easy route.

How to talk to your child about AI without scaring them

Children are picking up mixed messages: glossy adverts talk about “AI for everything”, while school assemblies warn that AI can get them disqualified. Parents can help turn that confusion into a calm, honest conversation.

A few starting points:

Acknowledge that the temptation is real.

Telling a stressed teenager, “Just work harder,” is rarely helpful. Recognise that long homework, anxiety and perfectionism make shortcuts appealing.Frame it around trust and long‑term goals.

Explain that qualifications are less about pleasing a teacher and more about building skills their future self will need. If AI does the hard thinking for them now, they pay for it later.Make it clear you’re not “anti‑technology”.

Position AI as a powerful tool that must be used like a sharp knife in the kitchen: incredibly useful, but with rules to keep everyone safe.Invite them to show you what they already do.

Sit down together and let them demonstrate their favourite apps. Then, gently map those uses onto the red/amber/green categories.Agree a “no secrets” rule.

If they are unsure whether something is allowed, the family rule can simply be: “If you’d be embarrassed to tell your teacher exactly how you did it, that’s a sign not to do it.”

If you discover that your child has already used AI in a way that might breach rules, deal with it early and calmly. In many cases, a pupil owning up before formal exams begin leads to a warning and some guidance rather than formal sanctions.

Practical steps parents can take this term

You don’t need to become a technology expert to protect your child’s grades and confidence. A few concrete actions make a big difference:

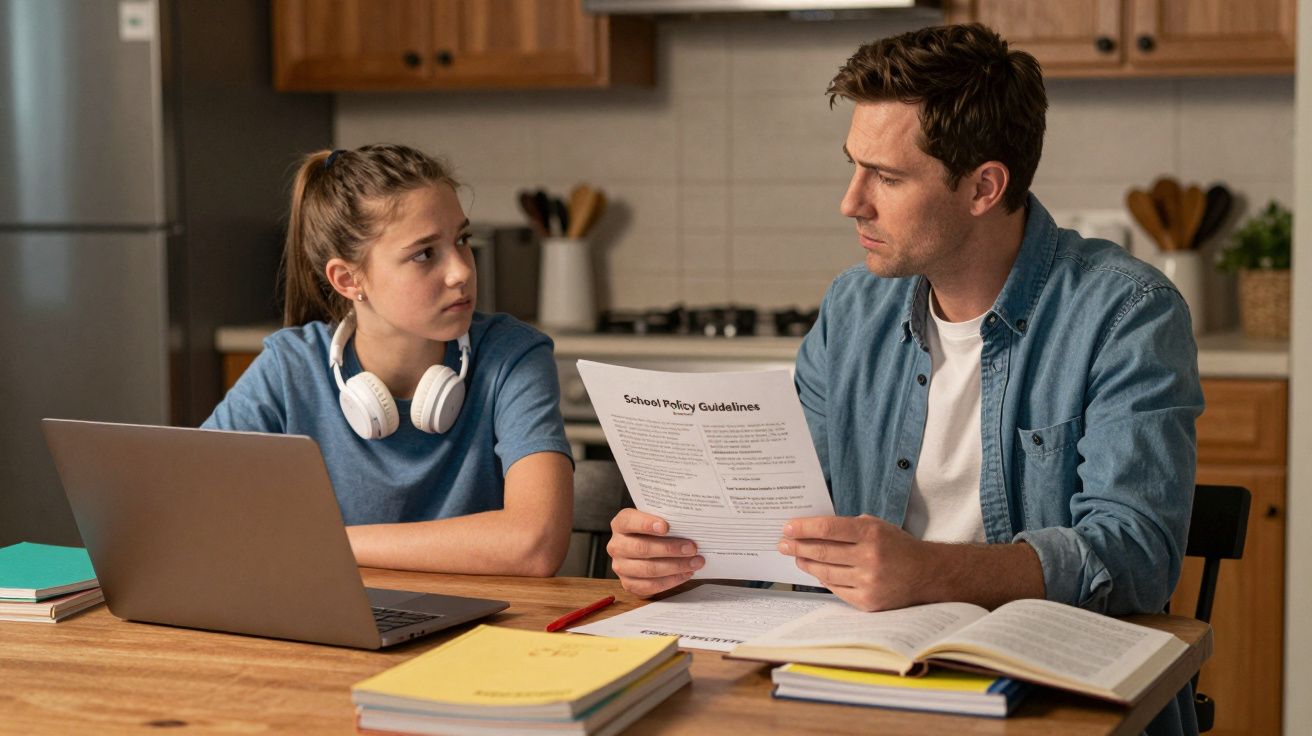

Read the school’s AI or academic integrity policy together.

Many are now on school websites or sent via email. Highlight anything that mentions “unauthorised assistance” or “AI tools”.Help your child build “evidence of effort”.

Encourage them to draft on paper sometimes, save versions of documents, and keep rough notes. This protects them if they are wrongly suspected of using AI.Normalise asking teachers.

Role‑play simple phrases like, “Sir/Miss, is it okay to use an AI app to check my grammar on this, or would you rather I didn’t?” Confidence in asking early prevents problems later.Offer alternative support.

If your child is reaching for AI because they feel lost, consider extra explanations from you, an older sibling, a school‑approved revision site or – if needed – a tutor.Keep perspective.

A single AI‑tainted homework is not the end of the world. Use it as a teachable moment about judgement, honesty and digital tools that will be part of their adult life.

FAQ:

- Is my child allowed to use ChatGPT or similar tools at all?

In most schools, yes – for learning (explaining topics, practice questions) rather than for producing assessed work. The line is usually drawn at using AI to generate content they then submit for marks. Always check the specific school policy.- Can AI‑detection software wrongly accuse my child?

Yes, AI detectors can produce false positives. However, teachers and exam officers rarely rely on them alone; they combine them with common sense, knowledge of the pupil, and, if needed, follow‑up questions. Keeping drafts and notes is the best protection if your child’s work is ever queried.- Is using Grammarly or built‑in spelling and grammar tools allowed?

Often yes, particularly for routine homework, but some schools set limits for high‑stakes coursework. Treat advanced rewrite suggestions with caution and check school guidance. If a tool is heavily changing the phrasing, your child should ask their teacher first.- What about UCAS personal statements and college applications?

Admissions teams expect these to be in the applicant’s own words. Using AI to brainstorm ideas or remind them of experiences may be acceptable; asking AI to write the statement, then editing it, is not. If an application feels generic or unlike the student, it can raise doubts.- Should I tell the school if my child has already used AI in the wrong way?

If it relates to minor homework and there are no formal consequences yet, you might start with a conversation at home, then encourage your child to clarify future use with their teacher. If the work in question is significant coursework or has already been challenged, it is better to be honest early; schools generally respond more constructively to openness than to concealment.

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment